Northanger Abbey, chapter 1: An Education

Catherine has my deepest sympathies.

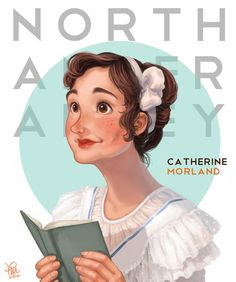

In actuality, something that has always struck me is how modern Catherine’s ordinary life sounds. “She [is] fond of all boy’s plays” and enjoys “the pleasure of mischief.” She tries to learn the pianoforte but ends up hating it. She likes to draw, but has no talent for it. She can’t stand math—“she shirk[s] her lessons.” And I love seeing a girl being interested in sports be portrayed as hopelessly normal rather than a shocking anomaly that worries her parents. Anyway, that’s Catherine at 10.

Catherine at 15 blossomed when “[h]er love of dirt gave way to an inclination for finery, and she grew clean as she grew smart.” Besides becoming pretty, she develops a taste for the same literature she ignored throughout her childhood. She commits to memory a bunch of “quotations which are so serviceable and so soothing in the vicissitudes of [heroines’] eventful lives.” This is part of her “training for a heroine.”

The “soothing” snippets of contemporary literature include lines from Shakespeare plays and popular poems of the time. All the quotes seem to be connected by a similar tone of heightened emotion. But the most obvious thing about them is that they are all taken out of their original contexts, which implies to my mind that Catherine likes the quotes because of their passion and agony, rather than because of the works themselves. I think this is decent foreshadowing of her biggest flaw: she fails to examine things in their full contexts, which leads to her making false conclusions. It might also be a comment on Catherine having a short attention span, although given that she will become a devoted reader of The Mysteries Of Udolpho, which I gave up on by chapter 7, maybe I don’t have a leg to stand on here.

Let’s move on to Catherine at 17. By this time, she has realized both her desire to be a heroine and that she also “[falls] short of the true heroic height.” In other words, she continues to be woefully average. However, the one sticking point is that this burgeoning heroine lacks a hero: she has yet to “[see] one amiable youth who could call forth her sensibility” or who “inspired one real passion.” No neighborhood lords or squires with eligible sons, no orphan with a mysterious past that was left on someone’s doorstep .. what’s a heroine to do?

Well, in the real world, luck doesn’t mean being the third son in a fairy tale or a changeling in a bassinet—but it does mean having a pair of childless neighbors who will invite you on their vacation to a popular spa town. Even for a small-time heroine like Catherine, “[s]omething must and will happen to throw a hero in her way.” Bring on the seaweed wraps!

Introducing the Shapard Shelf (or annotations from David M. Shapard I find informative but couldn’t fit anywhere else): the poets Austen quotes from are, in order, Alexander Pope, Thomas Gray, and James Thompson; “Love of poetry,” he notes, “would be highly suitable for a sentimental heroine[.]” Bath was/is a popular spa town because of its natural hot springs; it’s also the place where Austen’s father passed away. And this book includes one of the first usages of the word “baseball,” which Catherine plays as a kid before her “training for a heroine” begins.

How wonderful to see you resume these posts! I can't wait to read your comments on Northanger Abbey. Anticipating lots of fun. 8-)

ReplyDeleteMA

So happy to see you back and inviting us to read one of my favorite works with you! I took a moment to read The Beggar’s Petition and The Hare and Many Friends. Interesting themes to introduce in Chapter One!

ReplyDeleteI'm so glad you're back! I love reading your interpretations of Jane's books. I always get something new from your essays.

ReplyDelete