Mansfield Park, ch. 13: La La Land

|

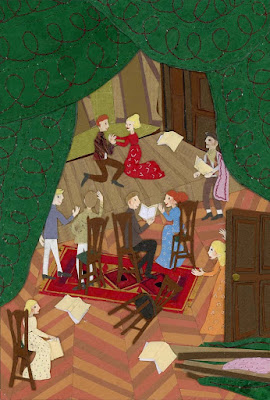

| Credit to Imogen Foxwell. Who's that in the corner by herself, I wonder? Hmm ... |

Everyone’s all, tell me more, tell me more. Yates, having found his people, obliges, and soon there’s buzz about how cool it’d be to put on a show on their own. Tom is suddenly all about the acting life. Seriously, this comes out of nowhere. I imagine that Tom is bored, restless, and maybe feeling left out of all the heterosexuality coupling that’s going on.

Seconding him is Henry Crawford, who is enthusing that they “be doing something,” even if it’s just a handful of lines. Reading this makes me think of the director’s commentary of Pride & Prejudice (2005), in which Joe Wright remarks that “things must have been boring back then.” And … I think there’s a little truth to this? Whatever the faults of the characters, they are also young, full of energy, and still figuring out life. I don’t blame them for wanting to do something to break the monotony of dinners, visits, and walks/rides across the park. I don’t see them as acting spoiled, either. Careless, yes, but spoiled? No way. You do you, Bertrams.

|

| The Drury Lane Theatre. Someone tell Tom Bertram that this is not supposed to be recreated in his father's house. |

Then Tom completely undercuts my point by measuring for a theater curtain. Thanks, Tom. Mr. Yates starts raving about constructing backdrops and painting scenery for the “stage.” This extravagance is what finally makes Edmund remind these “gentlemen and ladies” that they all have “the disadvantages of education and decorum to struggle through.” Edmund insists that well-bred people should not take on the job of acting, which is in accordance with the rules of what is right and proper. (Actors during this time didn’t have stellar reputations or follow the same rules as well-bred “gentleman and ladies.”)

But the discussion of play-acting continues later that evening, as Tom decides that the billiard room is better-suited for being a stage than for billiards. He goes so far as to designate Sir Thomas’s study as a greenroom, which takes it a step too far. Making over a room that belongs to your dad (without him knowing!) is either a sign of having major balls or a complete lack of foresight. Once again, Edmund points out the obvious: Seeing performances of plays and reading plays is all well and good, Tom, but putting on a performance (and without the head of the household present to consent and monitor everything) would be improper.

Tom’s excuses: no one’s going to advertise the performance, they’d all be better off reciting the “elegant written language of some respected author” than prattle on with their own, and it would keep their mom from her constant worrying about Dad. Geez, Edmund!

At which point, Lady Bertram jolts awake from her slumber. Tom concedes that his last point was bull, but maintains that they “shall be doing no harm” in putting on a play. Edmund protests again, saying that Sir Thomas’s “sense of decorum is strict,” which, even given the relative little we’ve seen so far of Sir Thomas, I think we can all agree with. So why doesn’t Tom?

Tom is all, look, baby bro, I’ll watch over my sisters and I’ll take care of this house, I have a vested interest in making sure it’s not harmed, and I’ll spend as little money as possible so that I can save Dad the expense, okay? GOD, Edmund, who died and made you king? Sorry I basically gambled away your future but what do you want me to DO, Edmund? I CAN’T BUY YOUR LIVING BACK EDMUND! STOP REMINDING ME ABOUT THAT!

Tell me that that’s not the subtext we’re working with here.

Let’s look at what’s been happening in Tom’s life recently: after spending an unhealthy amount of his father’s money, he journeys halfway across the world, gets sent back without ceremony, and then wiles away his time hunting, gambling, partying, and making stupid friends. Tom has failed as a son and as a brother. Instead of learning from his mistakes, he does the very human thing of finding something that he can control—one that also lets him pretend that he’s performing the role that his father always wanted him to. By treating his dad’s house like a Jenga tower, he’s asserting his authority—physically moving furniture and designating rooms for new uses as if he’s already inherited them. When reminded by Edmund in so many words that he hasn’t done anything to earn respect, Tom lashes out at his brother (the Abel to his Cain), unwilling to concede that Edmund is, indeed, the better son.

… I just bummed myself out.

Anyway, after Tom leaves the room, Fanny (hi, girl!) suggests that nobody will agree on which play to put on before things get too far. Maybe this is just more conjecture, but I get the sense that Fanny has seen her cousins be petty and indecisive before, even if she’d never use those words to describe their behavior.

The next morning, though, Julia and Maria are “quite as impatient of [Edmund’s] advice, [and] quite as unyielding to his representation” as Tom would want them to be, which I’m sure makes him feel like he’s in the right. But the sisters are also aware of some measure of impropriety … which they quickly convince themselves is not a big deal. Julia thinks she’s in the clear because she’s single (and ready to mingle), while Maria believes that her engagement “rais[es] her so much more [than her sister] above restraint.” Got that? Yeah, me neither.

Henry arrives with the message that his sister is totally on board for the theatricals. Curiously, Maria shows that she’s well-aware of Edmund’s crush on Mary: the author describes her expression to her brother as, “Can we be wrong if Mary Crawford feels the same?” She anticipates Edmund will change his mind based on Mary’s opinion, which speaks to at least two points: 1) his courtship of Mary has been obvious, and 2) Maria’s own emotional state. And she’s not wrong to think this way, either! Right away, we see how Edmund’s logic twists itself to conform with this news: he sees how “the charm of acting might well carry fascination to the mind of genius.” And not only is the skill set of acting elevated in his mind, but also he thinks it’s just so nice of Mary to be so “accommodating” to the whims of his siblings. With his conviction now starting to break down, it’s almost no wonder that Mary thinks she can influence him to choose a different career. Almost.

And the cherry on this sundae? Mrs. Norris is fully swayed by her nephew and nieces, deciding that she might as well move into Mansfield so she can help them put on the play.

Next time: the Bertrams are all about the drama (and the comedy), Henry’s charm skills are a little rusty, and the sisters’ battle for attention heats up.

Comments

Post a Comment