Mansfield Park, ch. 31: The Proposal

|

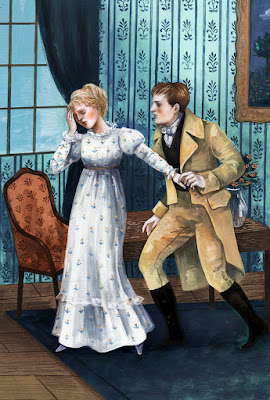

| Credit to Helena Perez Garcia. She made this scene way too real. |

Unfortunately, this does not star Sandra Bullock and Ryan Reynolds as surprisingly fresh twists on the opposites-eventually-attract romantic leads.

As Henry arrives at Mansfield, luck seems to be on his side: Lady Bertram leaves him with Fanny in the breakfast room. And this guy doesn’t waste any time. He reveals to Fanny that her brother William is now a lieutenant, thanks to Uncle Admiral wining and dining some high-ranking naval officers. It’s so easy to imagine Henry watching Fanny with a hungry look on his face as she reads the business letters he provides for her. After all, “he did not want her to speak”—he just wants to see her face light up. This could be interpreted as romantic or sentimental, and I have in fact taken this interpretation for granted in the past. But … well, let’s get to the main course.

Henry begins by congratulating Fanny and then launches into the process he went through to secure the promotion—a process that he leaves uncompleted, though he doesn’t give a specific reason why he had to leave London before he knew the promotion was in the bag (other than his own impatience). If you haven’t been noticing Henry’s lack of follow-through, try to look out for it from here on out. But now that he’s face-to-face with Fanny, he builds up to his proposal, talking about “twofold motives” and telling her “of his excessive and unequalled attachment to her.” Once Fanny cottons on to what he’s saying, though, it all goes pear-shaped. “Having twice drawn back her hand, and twice attempted in vain to turn away from him,” she finally says no. By my count, she says “no” about 13 different times in 12 sentences.

First of all, that is a lot of “no’s.” On top of that, she describes herself as “distress[ed],” his words as “unpleasant,” and twice says that she “cannot bear it.” Then she accuses him of “not thinking of [her],” implying that he isn’t taking her feelings or her protests seriously. Henry has been snatching at her unwilling hand and apparently circling her so she won’t be able to “turn away from him.” This is an absolute disaster of a proposal, guys. And what’s Henry’s takeaway from this after she literally makes a run for it?

“It was no time for farther assurances or entreaty, though to part with her at a moment

when her modesty alone seemed, to his sanguine and preassured mind, to stand in

the way of the happiness he sought, was a cruel necessity.”

This is the last bit of insight we get into Henry’s mental and emotional state for this chapter (talk about a cruel necessity). It’s so easy to miss because it’s one single sentence amid Fanny’s agitated and angry thoughts, so I imagine some first- or second- or even third-time readers might miss this and instead substitute their own, more generous interpretations of Henry’s romantic inclinations. I

mention this as a semi-likely possibility because …

|

| C.E. Brock provides us with a different angle of the proposal. It doesn't look much better. |

I was once a Hanny shipper.

I was thinking about when to make this confession, since I wanted to avoid spoilers in previous posts. But now is as good a time as ever. I was once very attracted to the idea of Fanny finding love with Henry, or at least, with someone like Henry. (Sorry, Ed.) I wanted Henry to help her laugh more. I wanted Fanny to impart some of her quiet wisdom to Henry. I wanted these two different characters to find happiness together. If Elizabeth and Darcy could do it, why not Fanny and Henry?

I no longer subscribe to that line of thinking. Now, Henry’s self-assurance infuriates me. Now, I am completely on Fanny’s side of the question. Her cluelessness makes perfect sense: “[W]hat could excuse the use of such words and offers, if they meant but to trifle?” she asks herself. Let’s not forget, she has seen Henry in action. She watched as he dismissed one of her cousins while openly flirting with the other. She knows Henry likes to “trifle.”

But because he can’t take a hint, Henry is back later that day to celebrate with the Bertrams and Fanny (William is still a lieutenant, after all). What’s more, he has a letter to deliver to Fanny from Mary … which is totally not at all suspicious or sneaky. I mean, come on. We all can guess that he told Mary about Fanny’s freak-out. So she writes this letter, invites herself to call Fanny by her first name, and declares “I chuse to suppose that the assurance of my consent will be something.” Now that is baffling. What makes her think that? Does she truly believe that Fanny trusts her more than she trusts Henry? What evidence is she basing that on? They are not friends. They do not confide in each other. See, if Mary had written: hey, my bone-headed brother made a bad call, but he’s crazy about you, take it from a sister who’s been waiting for her bro to settle down—then she might have a case. But she uses the word “consent,” as if she thinks that Fanny was waiting for her to give the go-ahead?

Okay, okay, I might be over-analyzing this. Maybe Mary is simply being witty and using “consent” with a touch of irony. Maybe she is trying to assure Fanny that her brother’s intentions are serious. But even then, I can’t shake the feeling that Mary is missing her target again. Her letter is so lighthearted, as if the snag in the proposal was a silly misunderstanding. Although if that’s the case, then Henry is the one to blame, and I owe an apology to Mary.

Even so, the letter has an even worse effect on Fanny’s emotional state. She’s so uncomfortable that she can’t eat or join in when Sir Thomas is talking about William. She can’t even look up for fear of catching Henry’s attention—not that he needs much encouragement.

~Interlude~

Mrs. Norris reveals that she gave William a tidy little sum at parting. Lady Bertram adds that she “only gave him 10 lbs.” And Mrs. Norris suddenly gets embarrassed, which seems to indicate either that she knows she should’ve given her nephew a bit more or that she’s shocked at how much Sir Thomas and Lady Bertram were happy to part with. I’m inclined to think it was the former. (BTW, £10 today would equal about £846, or $1,079. Austen would later reveal that Mrs. Norris gave William £1. I’ll let you do the math.)

~End interlude~

Fanny, all while trying to avoid Henry throughout the evening, is doubly confused, as now both Crawford siblings seem to be encouraging the engagement. But neither of them are trustworthy. Not only does she dismiss Henry as “everything to everybody” who can “find no one essential to him” (yikes! Henry needs a first aid kit for that burn), she also thinks Mary’s “high and worldly notions of matrimony” would prevent her from shipping Hanny. Fanny, remember, comes from a poor family on top of having been told again and again that she has little worth as a person; Henry is an independently-financial gentleman who runs in wealthy circles. Henry’s longing gazes at her, however, are making her have second thoughts about the whole thing (though she imagines that those looks are “no more than what he might often have expressed towards her cousins and fifty other women,” which just opens up another can of worms. Fifty women! Where are you getting that number from, Fanny?)

|

He urges her to W.B.F. to Mary, so Fanny bangs out a few lines that she knows “must appear excessively ill–written.” And you just know that Mary will read the note to Henry (if he doesn’t outright rip it open himself on the way back to the Parsonage, which at this point I wouldn’t put past him). Fanny must have similar thoughts, because she hopes that her note will result in “her being neither imposed on nor gratified by Mr. Crawford’s attentions.”

And that wraps up the second volume!

Soon to chapter: Henry has one more trick up his sleeve, Mrs. Norris’s plan for Fanny is foiled, and Sir Thomas has an unexpected confrontation.

Comments

Post a Comment