Mansfield Park, ch. 40: Those Who Can, Teach

|

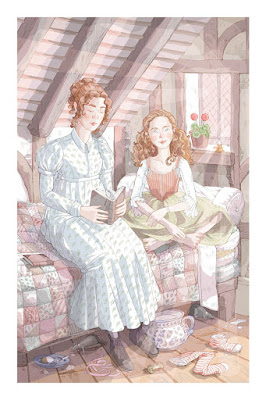

| Credit to Amree Weaver. Lookit that cute little face! |

We open with Fanny eager for Mary’s first letter, “a letter from one belonging to the set where her heart lived.” It’s more than Mary deserves, but Fanny can’t help how she feels after being cooped up in the Prices’ chaotic-neutral household. It’s so telling of Mary’s character that, in trying to remind Fanny of Henry’s love for her, she admits that she wouldn’t have bothered to write Fanny without Henry egging her on.

Mary also gives the 411 on two familiar faces. Julia is still plagued by Mr. Yates’ courtship while Maria has trouble “recovering the complexion from the moment [Mary] spoke of Fanny.” So … she knows. Mary assumes that, because “Henry could not have afforded her such a house” as Maria has in London, “[s]he will grow sober by degrees.” Just, um, you know that thing we do here with pins, right? Finally, Mary ends her letter the only way she knows how: by gleefully admitting that she will let Henry read Fanny’s reply letter without Fanny’s consent. It’s a relief that Fanny also writes to Lady Bertram, who appears to be (ironically, given her character) a regular correspondent.

But a more pressing issue then comes in the form of Susan, the fourteen-year-old sister (you know, the other daughter that the Prices ignore). Putting aside her inexperience in “bestowing kindness among her equals” and fear of “appearing to elevate herself as a great lady at home,” Fanny buys a new silver knife so that spoiled brat Betsey will stop fighting over it with Susan. Sweet baby angel Susan (yeah, I’m biased, okay?), tenderhearted and full of bluster, with a “determined character” that takes Fanny two weeks to warm up to and understand, is brimming with gratitude for this uncalled-for act of charity. And in a very short time, the two sisters actually begin to act like sisters: in talking, sewing, and reading together, “Fanny had peace, and Susan learnt to think it no misfortune to be quietly employed.” Astounding herself further, Fanny becomes that which all Janeites ascribe to be: “a renter, a chuser of books!”

I don’t think it’s an accident that Susan’s more intimate introduction immediately follows a letter from Mary that includes updates on Maria and Julia. Fanny judges that “[Susan’s] manner was … at times very wrong—her measures were often ill-chosen and ill-timed, and her looks and language very often indefensible.” Hm. Does that sound a little bit like a certain city girl we know? Of course, Mary is a lot of things Susan is not: witty, elegant, and carefree. Both characters “saw that much was wrong” in their respective homes. Mary uses her experiences as fodder for witty banter. Susan “want[s] to set it right.” Mary claims she knows how to “[speak] of Fanny like a sister should.” Susan knows how to treat her like one.

|

| Credit to Nan Cao. |

You know how Susan expects a “reproof” from Fanny due to “mak[ing] the purchase [of the knife] necessary for the tranquility of the house”? She knows it’s a bad look; she knows it doesn’t reflect well on her skill at running a household. In four paragraphs, Susan has shown more self-awareness than either of her Bertram cousins in the whole course of the novel. And the knife itself? Susan appreciates the knife she was given originally because it meant something to her (it’s a token of her deceased sister’s love for her). Unlike Mary and the rest of the Mean Girl squad, she doesn’t base the value of an object on how expensive it is. Like Fanny, she treasures her mementos.

Austen has created an enormous clap-back in the form of Susan. She has no guile, no education, no formal upbringing, and yet she possesses “so much better knowledge, so many good notions,” and has “formed such proper opinions of what ought to be,” that she has become the ultimate counter-example to all the Marias and Julias, and even moreso to the stuffy and high-brow Sir Thomases who think they know best. Fanny herself observes that Susan “had had no cousin Edmund to direct her thoughts or fix her principles.” This marks Susan as an outsider of the Price family, but not as an anomaly: she, Fanny, and William all learned in different ways how to build on their values and “principles” and the importance of setting things right.

Susan’s compressed introduction may be why she comes across as an afterthought in the novel. She has to serve as a foil to every female character in Mansfield Park, including her sister. At the very least, we need to digest how Fanny reacts to Susan: after earning Susan’s gratitude, Fanny uses it to encourage her sister, not take advantage of her. To teach and educate, not deride and ignore. With Susan, Fanny has a chance to break the cycle of abuse. And that’s just what she does.

Next chapter: Fanny expects to hear some very happy news (happy for some, at least), but instead has to deal with a gentleman caller who comes by way of London.

Oh, this was lovely.

ReplyDeleteI loved the part about the silver knife in your review, and how both Fanny and Susan cherish their presents. So well-written!

I've failed to catch that Susan is a great foil to Mary -- that is so true about them both seeing what is wrong in their home.

I've always loved how Fanny treats Susan and how close they become.

I got to say, I immensely enjoy the various illustrations, both professional and fan art. The first one is gorgeous, but I think Fanny and Susan's room is actually tidy and clean, even if it might be the only room in the house to be so.