Mansfield Park, ch. 44: Letter Go

|

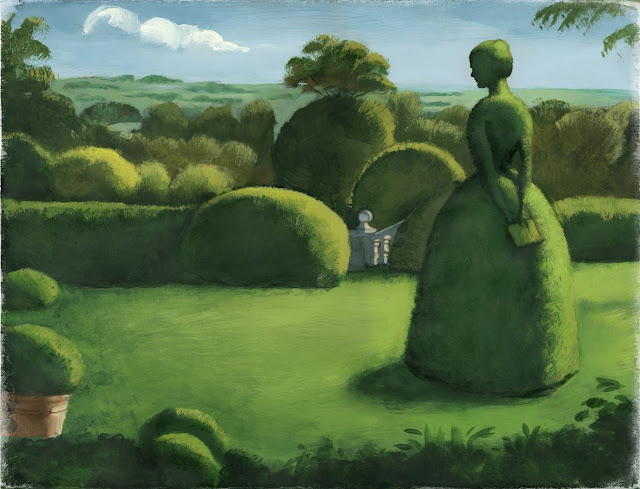

| Another beautiful illustration from Fernando Vicente. |

Guys. We have five more chapters to go. This is insane!

Ed just now finally decided to write to Fanny—from Mansfield, not London. To be fair, the poor guy has been wracked with agitation and uncertainty. While he is certain that he “cannot give [Mary] up,” that doesn’t mean it’ll be smooth sailing for them. Or that it has been: being in London (her natural habitat) has “altered” her behavior. It’s almost like she’s a completely different person, isn’t it, Ed? He places a lot of the blame on Mrs. Fraser’s influence, who, he observes, “places her disappointment [in her marriage] not to faults of judgment, or temper, or disproportion of age, but to her being, after all, less affluent than many of her acquaintance.” The irony of Ed wagging his finger at someone who blames others for her own unhappiness is so fitting. After all, he’s very content to blame others for “the weak side of [Mary’s] character” rather than take a close look at who Mary really is.

“When I think of her great attachment to you ... she appears a very different creature, capable of everything noble,” he adds, splintering Fanny’s heart. He’d rather that Mary reject him because he’s not rich enough for her tastes (and remember, it’s not like he’s penniless) than because of his job as a clergyman. I think I’ve documented their ongoing debate on that topic fairly well. He equates the importance of their union to that of Hanny’s, which says more about Ed’s state of mind than anybody else’s feelings.

Speaking of Henry, Ed paused his yearning for Mary long enough to observe how Henry and Maria reacted on their meeting: her behavior had “marked coolness” which caused him to “draw back surprised.” What made Ed recall Fanny’s words about Henry and his flirting is tricky to pinpoint. I think it speaks more to an anxiety about his sister’s feelings than Henry’s theoretical (to him) transgressions. He certainly implies that any “supposed slight” that Maria may feel is her fault and not Henry’s. And there he goes again, blaming everybody but the person who is failing to own up to his own actions.

Fanny’s reaction to all this? Well, she’s about as bitter as she’s ever been, certain that Ed will never see Mary for who she really is, and for that matter will always be on Team Henry. Her outburst gives some support to the notion that Fanny would accept Ed marrying another woman provided she had none of Mary’s duplicity and values. “Edmund, you do not know me,” Fanny proclaims, and it’s hard to argue with her. There is no doubt that Ed values Fanny (and at least a tiny bit of evidence in the letter that he values her more than he knows), but as long as he’s got stars in his eyes about Mary, he’s “blinded” to the true feelings of his best friend.

This is a depressing chapter. And there’s still more letters to get through. After the narrator is done with her sick burn re: rich wives with no lives, it’s revealed that Lady Bertram has some news about her son Tom. Our favorite ne’er-do-well gambler got drunk and took a bad fall, and some time after his friends left him (wow, insult to literal injury), he caught a fever. This is all elegantly communicated in the first letter. But in Lady Bertram’s second letter, we—and Fanny—see her discover for herself just how bad his condition is. And to make things worse, the trip to Mansfield affected his condition even more negatively. Good Lord, enough, Austen! We get it: don’t go on a drinking binge with your stupid friends! (Or be an irresponsible eldest brother in a Jane Austen novel, for that matter.)

Fanny, naturally, has to feel bad for him, especially as she considers “how little self–denying his life had (apparently) been.” That’s one way to put it, kid. Other than Susan, though, none of the other Price family members care, and the narrator gives another example of how siblings can “[feel] the influence of time and absence only in its” decrease in Mrs. Price, Lady Bertram, and the especially heartless Mrs. Norris.

Soon to come: Updates on Tom’s illness, Mary does more conspicuous recon, and Fanny has an epiphany.

Tom really has the most significant character development in the book, from what I can tell. Others may come to see the truth about others, especially recognising Fanny's value, but they otherwise stay the same, just a bit wiser. But Tom gets quite an overhaul. Much like Louisa Musgrove in 'Persuasion'; how many people do you reckon JA knew that were altered by a fall where they hit their head?

ReplyDeleteGood point! I wonder if JA was inspired to use a fall as a trigger for change in a character by something she knew about in real life.

DeleteSomehow, Tom's reformation is one of the things in this book that I could never believe. Even Louisa's change of character was more credible - for one thing, a severe concussion can cause long-term sensitivity (don't ask me how I know), and for another, Louisa is a bit of a chameleon - fitting her behavior to the man she is with. But Tom??? Well, perhaps the long illness... and then Maria's elopement, and the realization of his part in facilitating it...

Delete