Sense & Sensibility, chapter 2: Pick-A-Little, Talk-A-Lot

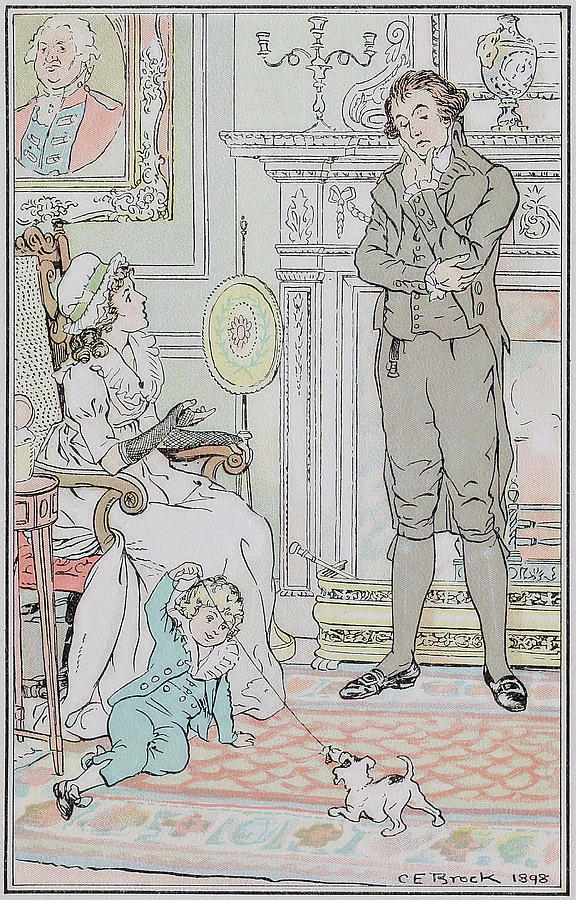

This is it. This is that conversation. John Dashwood and his wife decide the financial fate of the second Dashwood family in what feels like one fell swoop. It is a work of art, a testament to weak wills, serpentine logic, and selfish inclination. The arguments Fanny uses are compelling in their awfulness and horrifying in the effect they produce. So much so, in fact, that I’m going to be extra picky with this one.

The Dashwoods are staying at Norland for now, and while Fanny isn’t trying to push them out, she is concerned with her husband’s decision to give them 3,000 pounds. She begins her attack thusly:

To take three thousand pounds from the fortune of their dear little boy, would be impoverishing him to the most dreadful degree. [Fanny Dashwood] begged him to think again on the subject. How could he answer it to himself to rob his child, and his only child too, of so large a sum?

Little Henry will not miss a few thousand pounds coming out of his father’s fortune—especially when he’s a trust fund kid to boot, thanks to Old Dead Henry. And as David M. Shapard reminds us, being an “only child” would actually increase Little Henry’s wealth.

And what possible claim could the Miss Dashwoods, who were related to him only by half blood,

Get out of my Jane Austen book, Professor Umbridge.

which she considered as no relationship at all, have on his generosity to so large an amount? It was very well known that no affection was ever supposed to exist between the children of any man by different marriages …

John does have a relationship with his half-sisters, Fanny. They are siblings. They all share the same father. And here’s another Austen character trying to justify their reasoning by asserting that things generally work a certain way, with no room for deviations.

John explains that it was his father’s “last request.” Dr. Frances Dashwood provides the following diagnosis:

“He did not know what he was talking of, I dare say; ten to one but he was light-headed at the time. Had he been in his right senses, he could not have thought of such a thing as begging you to give away half your fortune from your own child.”

Oh, Mr. Henry was talking gibberish when he was thinking of the future of his second wife and his family.

John remains steadfast: “Something must be done for them whenever they leave Norland and settle in a new home.” And here’s where Fanny really starts to shine.

“Consider [...] that when the money is once parted with, it never can return. Your sisters will marry, and it will be gone for ever. If, indeed, it could ever be restored to our little boy…”

Yes, Fanny. What you just described is called a “gift.” It’s a thing people give out of love and kindness and from the goodness of their hearts. I understand if the concept eludes you.

“Why, to be sure,” said her husband, very gravely, “that would make a great difference. The time may come when Harry will regret that so large a sum was parted with. If he should have a numerous family, for instance, it would be a very convenient addition. … Five hundred pounds would be a prodigious increase to [the sisters’] fortunes!”

Now we see John start to mimic Fanny’s overblown concern for Little Henry and whatever sticky kids he might one day produce. Fanny encourages this by enforcing the conceit that John has “such a generous spirit” for a brother of either “half-blood” or full-blood status. I gag.

“I would not wish to do anything mean,” he replied.

Here’s your award for Minimum Decency, I guess???

“One had rather, on such occasions, do too much than too little. No one, at least, can think I have not done enough for them: even themselves, they can hardly expect more.”

And now he’s patting himself on the back for having already “done enough for them.” What’s he done so far? Well, he hasn’t kicked them to the curb. My hero.

Fanny then reframes the issue: “the question is, what you can afford to do.” John still likes the 500 pounds per annum idea, especially when he combines it with the sum of money the sisters will each get after Mom Dashwood dies. So he’s already thinking about how their other parent’s death will benefit his sisters. Lovely! Fanny replies,

“ … [I]ndeed, it strikes me that they can want no addition at all. They will have ten thousand pounds divided amongst them. If they marry, they will be sure of doing well; and if they do not, they may all live very comfortably together on the interest of ten thousand pounds.”

This presupposes that Mom Dashwood will die before the daughters marry, which would add to their respective fortunes and make them more attractive to prospective husbands. John decides this means he only needs to worry about Mom Dashwood’s fortune, so he suggests giving 100 pounds per annum. Fanny points out the very obvious flaw in this:

“To be sure, [...] it is better than parting with fifteen hundred pounds at once. But then if Mrs. Dashwood should live fifteen years, we shall be completely taken in.”

Mom Dashwood is forty. It would be extremely discourteous of her to live to at least 65.

“Fifteen years! my dear Fanny; her life cannot be worth half that purchase.”

I had to take several deep breaths and remind myself that I try to keep this a swear-free zone. John’s presumption that he can assess how much a life is “worth” speaks to his cold heart. And it should be noted that this “fifteen” number comes out of nowhere and has no basis in fact. Fanny explains:

“An annuity is a very serious business; it comes over and over every year, and there is no getting rid of it. … [M]y mother was clogged with the payment of three to old superannuated servants by my father’s will, and it is amazing how disagreeable she found it.

There’s nothing “amazing” about a stingy woman resenting having to pay a staff of servants.

… My mother was quite sick of it. Her income was not her own, she said, with such perpetual claims on it;

Yeah. It super-sucks that the people who serve you actually expect to be paid. This is something Mr. Ferrars understood, as he failed to leave his money to his wife “without any restriction whatsoever.” Otherwise she would have had to … set up the servants’ pay by herself? Gone without servants entirely? No one does that. Even the Dashwood women have servants. But John is struck by something his wife said:

“It is certainly an unpleasant thing [...] to have those kind of yearly drains on one’s income.

Even when that income is approximately 5,000 pounds a year, if not more. That’s right, folks: this is Bingley-level income. John is talking about 100 pounds (after having talked himself down from 500). For his step-mom. Who cannot earn more then 500 pounds from her fortune of 10,000.

One’s fortune, as your mother justly says, is not one’s own. To be tied down to the regular payment of such a sum, on every rent day, is by no means desirable: it takes away one’s independence.”

The only way John could become more independent and less beholden to others is if he moves to the Canadian wilderness, builds a log cabin, and takes hunting lessons from Ron Swanson. Not to mention the very real fact that his sisters had virtually no “independence” to begin with, not that he bothers to consider this point.

“Undoubtedly; and, after all, you have no thanks for it. They think themselves secure, you do no more than what is expected, and it raises no gratitude at all.

Fanny ascribes to the zero-sum theory of economics.

… It may be very inconvenient some years to spare a hundred, or even fifty pounds from our own expenses.”

500,000 - 50 = 499,950 pounds. So much inconvenience.

“I believe you are right, my love; it will be better that there should be no annuity in the case; whatever I may give them occasionally will be of far greater assistance than a yearly allowance, because they would only enlarge their style of living if they felt sure of a larger income, and would not be sixpence the richer for it at the end of the year. It will certainly be much the best way. A present of fifty pounds, now and then, will prevent their ever being distressed for money, and will, I think be amply discharging my promise to my father.”

Here John comes up with his own loop-de-loop of logic: if he provides the Dashwoods with a steady steam of money, they will feel compelled to spend it rather than save it. Better, therefore, to distribute it only when he feels like it. His reasoning is extreme to say the least, but the theme of spending vs. saving is one we’ll come back to and discuss more fully. For now, just know that John is deluding himself.

Then Fanny goes in for the kill.

“To be sure it will. Indeed, to say the truth, I am convinced within myself that your father had no idea of your giving them any money at all. The assistance he thought of, I dare say, was only such as might be reasonably expected of you; for instance, such as looking out for a comfortable small house for them, helping them to move their things, and sending them presents of fish and game …

It’s a miracle—she can read the minds of dead people! Clearly Mr. Henry Dashwood just wanted John to hire a U-Haul for his step-family and make sure they get a nice dinner once in a while.

… Altogether, they will have five hundred a-year amongst them, and what on earth can four women want for more than that? They will live so cheap! Their housekeeping will be nothing at all. They will have no carriage, no horses, and hardly any servants; they will keep no company, and can have no expenses of any kind! Only conceive how comfortable they will be!

Here’s a fun little pop quiz: guess how “comfortable” Fanny Dashwood would be without a mode of transportation, without guests, and with a bare-bones household staff.

… [A]nd as to your giving them more, it is quite absurd to think of it. They will be much more able to give you something.”

I am sincerely at a loss for this. Fanny provides no examples of what the Dashwood women might “give” to John. The only thing I can think is if one of them marries well, thereby giving John a respectable brother-in-law. But the chance of that happening with poor dowries is nil.

“Upon my word,” said Mr. Dashwood, “I believe you are perfectly right. My father certainly could mean nothing more by his request to me than what you say. I clearly understand it now, and I will strictly fulfil my engagement by such acts of assistance and kindness to them as you have described. When my mother removes into another house my services shall be readily given to accommodate her as far as I can. Some little present of furniture, too, may be acceptable then.”

My desk has a dent in it from where I’ve been banging my head. Remember, we started with 3,000 pounds and now we’re down to hiring College Hunks and gifting a coffee table. And we’re still not done! What follows is a discussion about letting the Dashwoods keep their silverware and dining sets (“A valuable legacy indeed!” exclaims John ). I need some Advil.

Fanny leaves us with this parting shot at Mr. Henry:

“Your father thought only of them. … [Y]ou owe no particular gratitude to him, nor attention to his wishes, for we very well know that if he could, he would have left almost everything in the world to them.”

John doesn’t owe anything to his father. I laugh with scorn. You’re on your own, dead dad! Even more gut-wrenching? This clinches it for John, as it “[gives] to his intentions whatever of decision was wanting before.” Lastly, he decides

… that it would be absolutely unnecessary, if not highly indecorous, to do more for the widow and children of his father, than such kind of neighborly acts as his own wife pointed out.

“Highly indecorous,” as if it would be improper to provide his poor step-family with a decent income. In later chapters, we’ll chronicle John’s reaction to those distant relatives and kind friends who do not see such obstacles in helping out the Dashwoods. For now, we’ll leave John and Fanny to count their money and quote Gordon Gekko at each other.

Next chapter: we introduce Edward Ferrars, and Marianne speaks her mind on matters of the heart.

The way John behaves in this chapter--letting himself be swayed by his wife and not having any more spine than cold spaghetti--makes me think of the Neutrals in Dante's Inferno: “Heaven will not have them, and the deep Hell receives them not lest the wicked there should have some glory over them.” They would pick a side and stand firm but were always influenced by which way the wind is blowing and so are doomed to follow an ever-shifting banner. John would be right at home.

ReplyDeleteMA

The servants that Fanny's mother has to pay are retired. They are no longer working. "[M]y mother was clogged with the payment of three superannuated servants by my father’s will." "Superannuated" means elderly. Fanny's mother is paying these three elderly servants a pension and her husband knew her well enough to know he needed to put that in his will. As wealthy as Mrs. Ferrars is, I'm sure she has more than three servants actually working for her.

ReplyDelete