Sense & Sensibility, chapter 5: Moving Right Along

I think the first thing to mention about this chapter—and it’s explicit in the text, so it’s not hard to miss—is that despite the suddenly sped-up process of moving out, Mama Dashwood is not trying to get in between Elinor and Edward. She invites Edward to visit them after they settle into their new house (she also invites John and Fanny, who do not take her up on this offer, but at this point we’re not surprised).

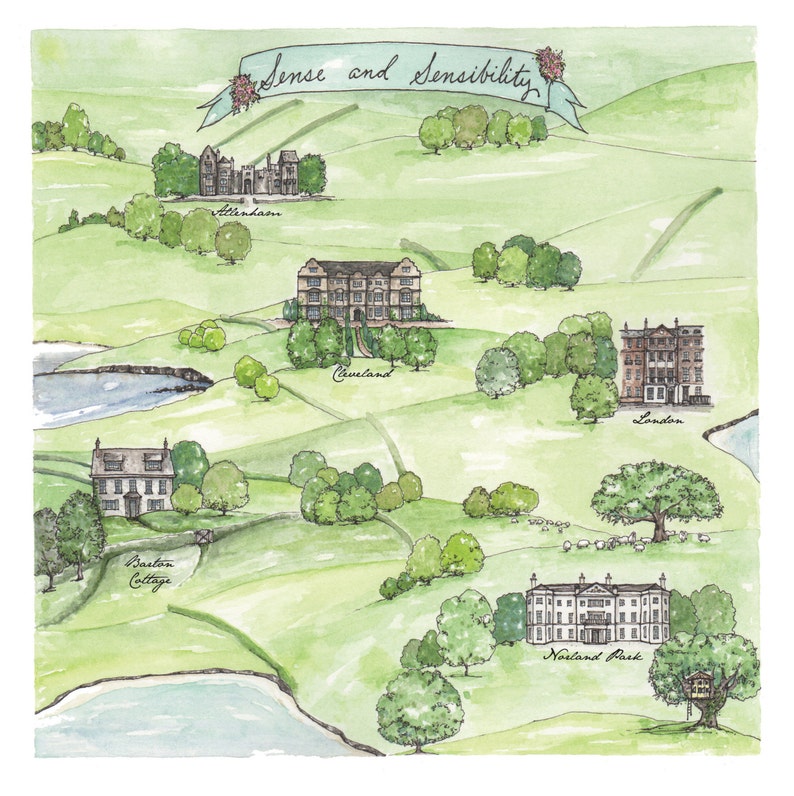

This American had to look on a map to really understand how far apart their home in Sussex (a region south of London) is from “within four miles” Of Exeter. There’s a lot of mileage between the two. It’d be similar to moving from a nice suburban house in New Jersey to a small town on the coast of Lake Michigan—a quiet place where there’s not much action (and near the shore). A downgrade in terms of social circles as well as social status.

Another rather prominent detail is that this is the first time we hear Edward speak: “Devonshire! Are you, indeed, going there? So far from hence! And to what part of it?”

Hold still, my beating heart.

The reason why he makes such a big deal about the location is not because of the distance. Men can travel independently, on horseback or on coaches, and Edward has the resources (though not his family’s blessing) to go where he wants. No, the reason has more to do with the proximity of Exeter to another place in Devonshire where Edward has been, but I’ll stop before I give away the whole game.

Turns out that Mama Dashwood can get a lot done when motivated by indignation, but again Elinor lends a helping hand. To get ready for Barton Cottage, the Dashwoods have to pick which servants to bring with them and decide whether or not to bring the carriage. Elinor gets her mother to sell the carriage, as it would save on upkeep (not to mention the fact that they don’t even own horses, a point that we’ll return to in the future), and they succeed in retaining 3 servants: “two maids and a man” (Mama Dashwood wanted more but was talked down). Shapard notes that since male servants were more expensive, this may suggest that Mama Dashwood got the male servant on the cheap due to her kindness as an employer. If that’s true, man, what a way to stick it to Fanny. Now she’s going to have to hire a replacement.

Now you may be wondering what Fanny and John think of all this. Well, they’re not quite as pleased as one might think. After offering “a cold invitation to [Mama Dashwood] to defer her departure,” Fanny washes her hands of her step-family and apparently has no real alarm about Edward’s feelings toward Elinor any more. She does take a moment to mourn the loss of some “handsome article[s] of furniture” that the Dashwoods are taking with them, since “Mrs. Dashwood’s income would be so trifling in comparison with their own” means, in her view, that Mama Dashwood shouldn’t get to keep them. Because poor people aren’t allowed to have nice things.*

John Dashwood is worse than his wife for once, as he evades carrying out his duty to help his step-family by incessantly complaining about “the increasing expenses of housekeeping, and of the perpetual demands upon his purse.” Mama Dashwood picks up on the subtext and finally accepts that their extended stay at Norland was all the generosity she was meant to expect from him. Hilariously, John expresses his dismay that they’re moving so far away that it “prevent[s] his being of any service to her in removing her furniture”—the only assistance he resolved on giving. He’s “vexed” that he can’t help out within the terms he has decided on (never mind that he could at least offer to pay for the shipping method).

Say goodbye to John and Fanny for now. We’ll see them later in a different setting and interacting with other characters. Having read the later volumes over and over, I think I can say that John Dashwood is this novel’s Tom Bertram, and I think I’ll be able to prove why later.

But the impression we’re left with has nothing to do with the couple and their petty feelings. Instead, we’re given a scene where Marianne “wander[s] alone before the house, on the last evening of their being there” saying goodbye to the foliage: “‘[Y]e well-known trees! … you will continue the same; unconscious of the pleasure or the regret you occasion, and insensible of any change in those who walk under your shade! But who will remain to enjoy you?’” This reflects several attributes of her character: there’s her sentimentality, her melodramatic tendencies, and a bit of her self-centeredness (like, you’re not the only one who likes a shady spot on a hot summer’s day, Marianne). But her genuine reverence for nature offers a counterpoint to her brother’s and sister-in-law’s materialism. Here, Austen uses Marianne as a spokesgirl for the Dashwood’s collective sorrow at having to leave the only home they ever knew.

In the next chapter, the Dashwoods deal with a reduced living space and new neighbors.

*Shapard: “The idea that one’s possessions should correspond to one’s income and social position was a common one” for this time period. However, he also notes that Fanny is being absurd about this.

Credit for the above watercolor goes to Kim. You can buy a print from her Etsy store.

Comments

Post a Comment