Sense & Sensibility, chapter 29: Now I’m Begging For Footnotes In The Story Of Your Life

There are some questions you only think you want the answers to.

This is how Marianne begins the chapter: convinced that once Willoughby explains his standoffish behavior at last night’s ball, they can get their great love affair back on track. Of course, this all hinges on the explanation he gives … and he doesn’t actually give one at all. He’s all, sorry if I offended you, hanging out with your family was great, I’m totally marrying this other chick, kthanxbi. He even describes his feelings for MA as “esteem,” using the very word that she herself scorned previously. “I entreat your forgiveness of what I can assure you to have been perfectly unintentional,” he writes, closing the door on their entire relationship. And he has obeyed her demand to returns all her letters and the lock of hair “which you so obligingly bestowed on me.”*

Insert hand into chest, clutch heart, rip from chest cavity. On repeat.

So Marianne, dying a thousand deaths, has to cry it out. Elinor is in complete sympathy with her and lets her cry for a time, as she believes that “such grief, shocking as it [is] to witness it, must have its course.” Notably, it is through Elinor’s eyes that the reader first sees Willoughby’s devastating letter and it’s her conclusion that “every line [is] an insult” that “[proclaims] its writer to be deep in hardened villainy” that we end on. Willoughby’s “cruel” and ungentlemanly disregard for MA proves, at least to Elinor, his lack of worth as a lover and husband; she’s downright relieved that they’re now separated.

Elinor brings up to MA that at least she can stop worrying about the state of this perilous engagement. And that’s when MA finally hits us with the truth: No engagement has ever existed and I can finally stop tearing my hair out. “He has broken no faith with me,” is how she puts it. “It was every day implied, but never professedly declared.” From Shapard: “A declaration of love was tantamount to a proposal, for a man normally never said that to a woman until he was asking her to marry him” (cf. Darcy’s proposal to Lizzy that he “admire[s] and love[s]” her). Since Willoughby was careful to never let the “L” word slip out, he’s not officially tied to MA and cannot be accused as abandoning her. At least, not by society at large. (The issue of whether he did love her is still a mystery at this point in the narrative.)

The reveal that there has been no real engagement puts both MA’s actions and Willoughby’s response in a different light. She vaguely justifies her letters to him: “[C]ould that be wrong after all that had passed?” (Another question she probably doesn’t want an answer to). Her second justification has more merit: “I felt myself [...] to be as solemnly engaged to him, as if the strictest legal covenant had bound us to each other.” Given that this entire chapter illustrates the strength of her feelings, her conviction on this point is convincing, even as she disregards any adherence to propriety. Her letters to Willoughby also show her clear expectation that he’d visit her in London. And most damningly, she at last explains that Willoughby himself told her “it might be many weeks before we meet again,” phrasing that heavily implies that he believed/planned on seeing her at some point in the future (though neglecting to specify the context of that meeting). No wonder a lovestruck MA would assume that he was pushing the pause button on their relationship, rather than the self-destruct button. She thought the distance between them was the only thing stopping them from being together.

MA, struggling to think critically, insists that someone must have convinced Willoughby that she never loved her. In one letter she wrote, “You have perhaps been misinformed, or purposely deceived, in something concerning me.” To Elinor she protests, “[I]s there a creature in the world whom I would not rather suspect of evil than Willoughby, whose heart I know so well?” Again with the questions that you probably don’t want to know the answers to, MA. The existence of this new fiancée of his (who, curiously, goes unnamed in the letter) is yet another shock to her system, and she switches between blaming Willoughby and blaming this other woman. “Whom did I ever hear him talk of as young and attractive among his female acquaintance?” MA moans, unable to consider that, well, why would he talk about another cute girl in front of the girl he was courting? But the larger point here is that there’s a lot about Willoughby that MA didn’t know and still doesn’t, which is Willoughby’s true agenda. He has made it difficult for her, and for Elinor to a lesser extent, to think critically of him.

MA has a lot to grieve about, which Elinor understands—but she’s also seen the physical toll that MA’s anxiety has taken on her during the last several days, and it’s perhaps because of this that she tries to rouse her sister. “[Let others see] how nobly the consciousness of your own innocence and good intentions supports your spirits,” Elinor urges (who takes her own advice). MA is apologetic that she’s causing Elinor distress, but insists, “[M]isery such as mine has no pride. I care not who knows that I am wretched.” She’s equally insistent that Elinor can rely on Edward’s enduring love, which reads both as sisterly kindness and a way for MA to live vicariously through her sister’s (apparently) uncomplicated love life. Elinor’s protests and pieces of advice go unheeded—for now.

MA begs to go home to Barton Cottage: “I cannot stay to endure the questions and remarks of all these people. The Middletons and Palmers—how am I to bear their pity?” Never mind her claim that she didn’t care who knows about her “misery”—turns out she minds a little bit. It’s worth pointing out two things: a) that MA has been a very rude guest to Mrs. Jennings, trashing her in one of her letters to Willoughby and insisting that they leave their hostess willy-nilly, and b) Mrs. J has demonstrated a complete lack of discretion regarding MA and Willoughby’s relationship status. Mrs. J adamantly tells Elinor that she’s been forwarding gossip about the engagement for weeks (despite the fact that nothing was formally announced) and laughs in Elinor’s face when she tells Mrs. J that she’s being “unkind” in spreading such rumors. MA senses she’s being used as gossip fodder and, like Elinor, does not appreciate it. This doesn’t justify her rudeness, but I think it’s an explanation.

But soon we will see another side of Mrs. J as the Willoughby fallout continues.

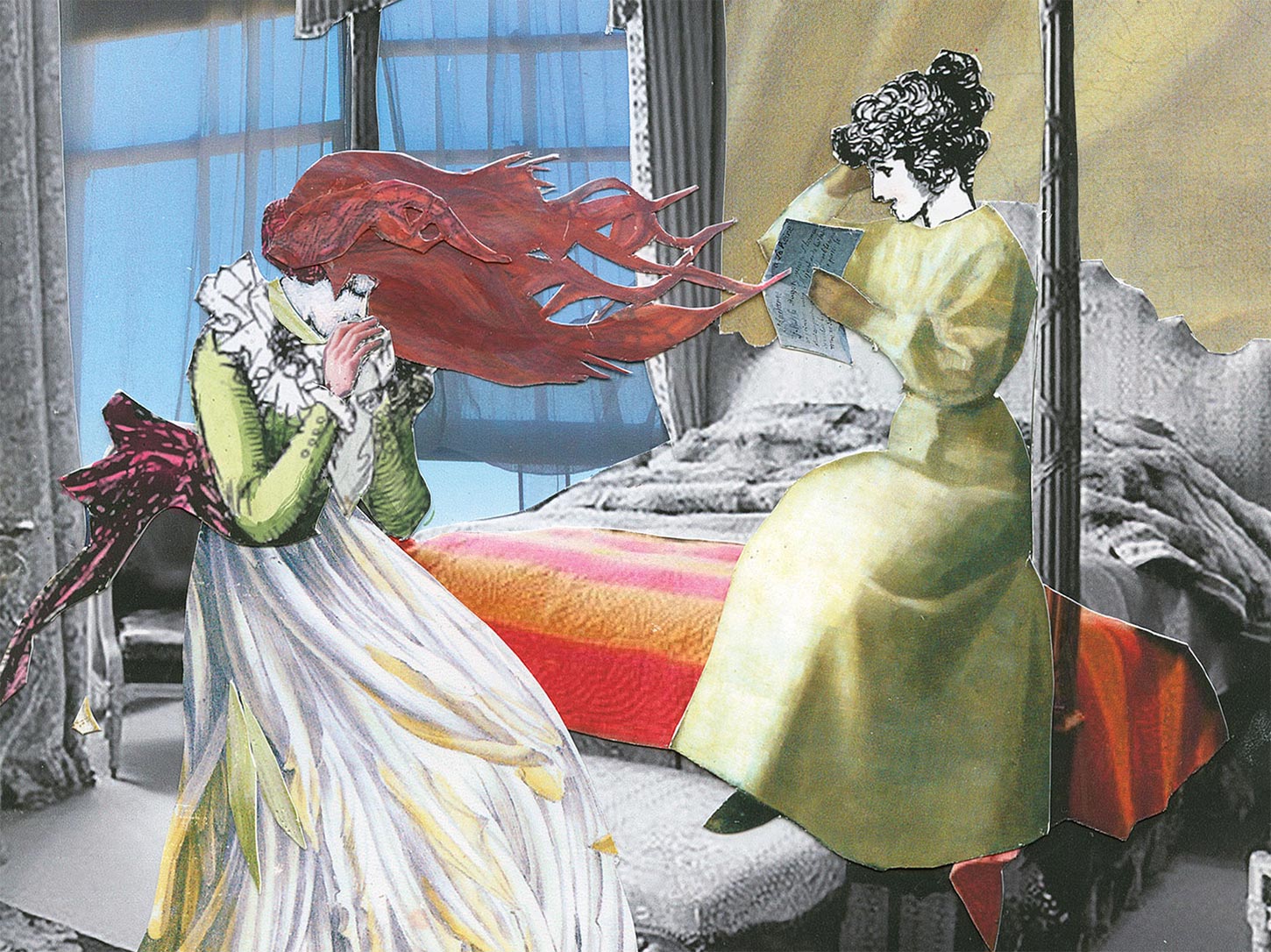

Credit for the above illustration goes to Augusta Talbot.

*We will discuss the true author(s) of the letter in a future chapter.

Comments

Post a Comment