Sense & Sensibility, chapter 37: To Tell The Truth

Welcome to the chaos.

Typical for a Jane Austen novel, the true action takes place off-stage while the narrative centers its characters in the immediate aftermath—and when I say immediate, I’m talking day of. Yes, my dears, Lucy and Anne Steele are unceremoniously kicked out of Fanny Dashwood’s household and Elinor hears about it on the same afternoon. Equally distressing? Lucy’s secret engagement to Edward is no longer a secret.

So to sort out the different feelings of each character toward Lucy, Edward, and Fanny (truly the biggest victim of all here, no contest), we’re going to take things one at a time.

Mrs. Jennings: Firmly on Team Lucy, she praises Edward for standing up for her cousin and begins to micro-manage their theoretical household before the day is over. If you didn’t like Mrs. J before (how is that even possible), then surely you’ll appreciate her passionate reprimand to John when he bemoans Edward’s decision to stick with Lucy. It really is a remarkable moment between the two people-pleasers that reminds the readers that despite Mrs. J’s limited intellectual powers, she values family and emotional connection more than some people do. Speaking of …

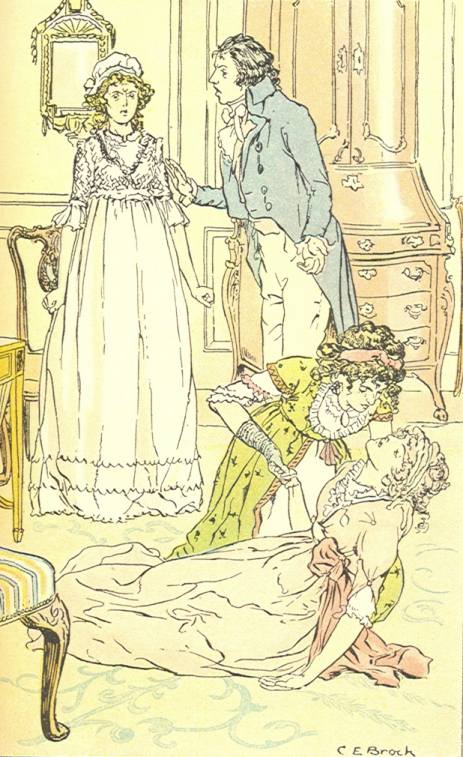

John Dashwood [pause for boos]: Boy, is this dumb-dumb in a pickle. According to Mrs. J’s secondhand account, he had to actually plead with Fanny (on his knees!) to at least let the Steele sisters pack their bags before kicking them out. YIPE. On top of this, he insists that “[s]he has borne it all, with the fortitude of an angel,” although naturally “she never shall think well of anybody again.” His talk of deception and abuse rings even more false given that the only person who has actually suffered at Lucy’s hands has been Elinor; Fanny voluntarily invited the Steeles to stay because she’s Lady Catherine de Bourgh in training. It’s fun (but not as fun as it could be) to see John backtrack after he implies that Edward should have thrown Lucy away. It’s really Mrs. Ferrars who holds power over Edward, cutting ties with him and cruelly threatening to “do all in her power to prevent his advancing in” his career (as long as that career isn’t the church). John bemoans Ed’s “stubborn” persistence, absolutely clueless that his audience only sees coldness, greed, and naked manipulation in Mrs. Ferrars’s treatment of her son.

To be clear, Edward’s big, unforgivable act isn’t so much the secret engagement as it is that Lucy Steele does not have Miss Morton’s dowry or connections.

Elinor: At last, Elinor gets to have her say. In breaking the news to MA, she also comes clean about being “forced” into Lucy’s confidence and living with this knowledge for the last four months. In her desire to “acquit Edward” of being “a second Willoughby,” she explains how she has used that time to reflect on the bad news and conclude that she’s “so sure of [Edward’s] always doing his duty, that though now he may harbor some regret, in the end he must become so.”* When MA cruelly suggests that Elinor feels little for Edward, Elinor snaps back with her biggest (only?) passionate speech in the novel. “I have had [Lucy’s] hopes and exultation to listen to again and again,” she says. “I have had to contend against the unkindness of [Edward’s] sister, and the insolence of his mother.” She goes straight to MA’s heart: “[I]f you can think me capable of ever feeling, surely you may suppose that I have suffered now.”

She also explains that her current “composure of mind” is “the effect of constant and painful exertion” of her situation. The solution has been her sense of duty, of what she owed to MA and Mama Dashwood (and Maggie, who may often be silent but is no less a loved sister). This passage has the dual effect of a) indirectly rebuking MA for her wallowing, which hasn’t been good for her or the people who love her, and b) linking Elinor to Edward in their shared values, although in this case Ed’s duty pulls him away from his family, while Elinor’s duty serves herself as while as her mother and sisters.

Marianne: Our Romantic drama queen feels her sister’s betrayal more strongly than Elinor (will let) herself. That Lucy is “so absolutely incapable of attaching a sensible man” makes it hard for her to believe that sometimes, men of sense get stuck with a silly wife no matter who says otherwise. Then, after Elinor’s confession sobers her up (“Because your merit cries out upon myself, I have been trying to do it away”), she gets with the program, promising to behave herself in front of their relatives and Lucy Steele. “[W]here Marianne felt that she had injured, no reparation could be too much for her to make,” the narrator assures us, and indeed not only does MA stay true to her word, but also the “heroism” she displays gives a much-needed lift to Elinor’s spirits. And interestingly, when MA finally has an outburst once John leaves, Elinor (as well as Mrs. J, MA’s secret twin) follow suit. It goes to show that emotional outbursts do have their place—they give relief to pent-up feelings and can be bonding experiences. It’s only when you allow passionate feelings to take over your life that they start seriously messing you up.

Next time, we’ll catch up with Anne Steele as she gives Elinor a life update.

*In attempting to be diplomatic about Lucy, she refers to her as “a woman superior in person and understanding to half her sex,” which, hilariously, is another way of calling her basic.

I really started to like Mrs. Jennings when she saw through Willoughby's horse-manure. Even Elinor will be ready to be sorry for him, caught between a rock and hard place. But Mrs. Jennings? "when a young man, be who he will, comes and makes love to a pretty girl, and promises marriage, he has no business to fly off from his word only because he grows poor, and a richer girl is ready to have him. Why don't he, in such a case, sell his horses, let his house, turn off his servants, and make a thorough reform at once?" She sees clearly - that Willoughby, despite being caught by Miss Smith, does indeed have an option - his abandoning Marianne is not because of his lack of options, but because of his selfishness. From here on I like Mrs. Jennings more and more. She's vulgar, she's ridiculous, but she's kind and she cuts to the truth.

ReplyDeleteElinor's defence of Lucy as "superior to half her sex" rings false. Yes, Lucy is clever; but she is also selfish and cruel, and Elinor has had personal experience of both qualities. So why is she defending Lucy? Is it her pride, so that Edward won't come out as a complete loser? And does she really think Marianne will believe her? I vote for pride.

ReplyDeleteI read it as Elinor’s trying to rationalize how Edward hasn’t completely ruined his life: “Lucy is average, but she could be worse.” At least she’s not like Anne, for instance. Elinor is definitely trying to look on the bright side.

DeleteYes, she is. But personally, I'd take Anne over Lucy any day. Yes, Lucy is much more intelligent than Anne, but Anne is just stupid, while Lucy is malicious and cruel. I think marriage to Anne could be managed, pretty much like Charlotte's marriage to Collins, by being elsewhere whenever possible, while marriage to Lucy would be constant torture.

DeleteBut I definitely agree that Elinor is trying to see the brighter - or less dark - side, for Edward if not for herself. It's just not a good idea to try that kind of cover-up with Marianne, poor Elinor.

Delete