Sense & Sensibility, chapter 38: The Lesser Of Two Steeles

Good girls don’t get to have fun in Jane Austen novels.

Look, objectively this isn’t an accurate statement—a casual read-through of Pride & Prejudice refutes it. But man, if it were up to Elinor, she wouldn’t know anything about what’s going on with Lucy and Edward. She has to be forced into gossiping by Mrs. J and Anne—and this is before Lucy herself uses her as a conduit to appeal to Mrs. J’s sympathy. If this was only Austen book you ever read, you might be left bewildered at Elinor’s relative lack of curiosity in the goings-on (and miss the nuance about proper conduct and respecting others by acting with dignity, a quality many of the more entertaining characters lack).

Say what you will about the Steeles (I have, and will continue to), but they get stuff done. Arguably they have to get stuff done because of their low position and they’re just smart enough to know how to network. And you can also argue that they’re crude in their methods of sucking up and playing on others’ egos. This didn’t work out for them when Anne told Fanny Dashwood about Lucy’s engagement, but we all know that Anne has trouble reading the room in general.

So why do I kind of prefer her to Lucy?

A couple of reasons. First of all, Anne is not Lucy, who “force[s]” her friendship onto Elinor in a particularly painful and insincere way. Second of all, Anne is a thirty-year-old woman going through the motions of a superficial teen girl (gabbing about her fake boyfriend Matt Smith Peter Capaldi David Tennent) and I can’t help but feel bad that she’s stuck in arrested development. Third of all, she’s described as “looking rather shy” when she meets up with Elinor after falling out with Fanny, reminding us that she and Lucy’s vulnerable position means they might be essentially blacklisted thanks to Fanny’s fury. (Even though Anne’s tattling wasn’t smart, it’s Fanny’s fault that they were temporarily homeless.) So, yeah, I can spare some sympathy for her.

And even though Elinor rightly chastises her for gossiping about Lucy and Edward’s literally-behind-closed-doors conversation, it’s kinda satisfying having a firsthand account of the lack of love between the couple. There was consensus among their social circle that Ed would cast Lucy off in favor of Miss Morton. “[Edward] said it seemed to him as if, now he had no fortune, and no nothing at all, it would be quite unkind to keep her on to the engagement … for he had nothing but two thousand pounds, and no hope of anything else,” Anne snitches. Not even a living would be enough for two people, he protests. But once Lucy assures him that she has no intention of letting him out of the engagement, “he was monstrous happy.”

Anne Steele, licensed couples therapist, everybody.

Then she tattles on herself by revealing that she’s repeating a private conversation, justifying this by further revealing that Lucy would often listen in on her private conversations, and I am stuck between wanting to give her a smack upside the head and to rescue from her horrible sister.

Contrast Anne’s incessant gabbing to the insincere tone of the letter Elinor later receives from Lucy. “[Edward] would not hear of our parting, though earnestly did I, as I thought my duty required, urge him to it for prudence sake,” she writes, adding that “he did not regard his mother’s anger, while he could have my affections.” Absolutely false, as we and Elinor know thanks to Anne’s report. Lucy’s “real design” in sending the letter is to suck up to Mrs. J (and it works like a charm, because Mrs. J is who she is). Blech, right?

Call me crazy, but I prefer Anne’s direct approach in this matter: “tell [Mrs. Jennings] I am quite happy to hear she is not in anger against us […] and if […] Mrs. Jennings should want company, I am sure we should be very glad to come and stay with her for as long a time as she likes,” she tells Elinor. Perhaps it’s less dignified, but it’s more honest and less forceful. Anne’s just asking Elinor to pass on a message. Lucy, however, crows about how she’s got Ed now, lies about how much he actually loves her, and simpers about how much Elinor’s silence friendship has meant to her.

Make no mistake: Anne lacks morals and grace. But Lucy offends me more because she doesn’t possess those qualities either, yet she pretends she does. She pretends to Edward. She pretends to Elinor. She pretends to Mrs. J. And that’s why Lucy will get farther in life. Anne doesn’t bother, and while she’s rude and superficial, she doesn’t try to harm others. Kind of like an overgrown puppy that desperately needs house-training: frustrating to deal with on a daily basis, but you can’t really blame her. Look at who she’s got for family.

Join me next time as the Dashwoods discuss leaving London behind and Col. Brandon makes an offer that can’t be refused.

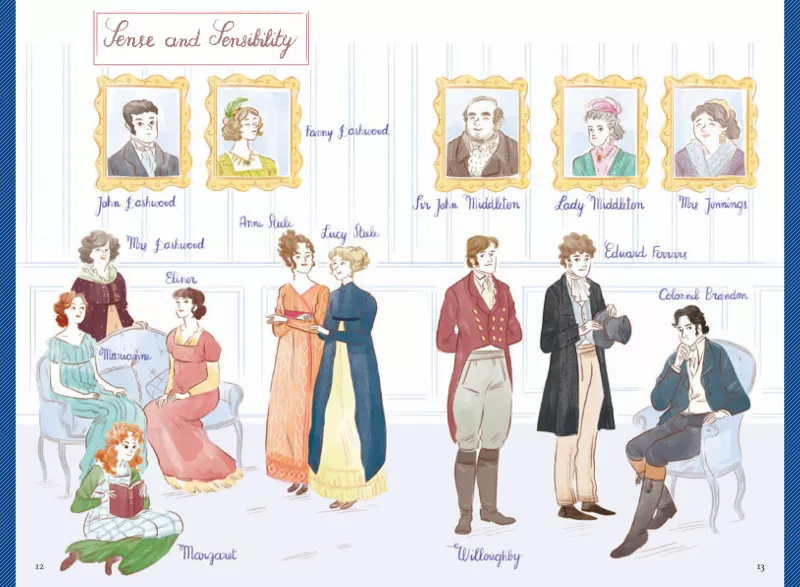

Credit to Sara Menetti for the above illustration.

Lucy's scheme to suck up to Mrs. Jennings works like a charm not only because Mrs. Jennings is who she is, but because Elinor is who she is - grasping Lucy's machinations at once, and facilitating them by handing Mrs. Jennings the letter. Which brings me to a perplexing question: why does Elinor choose to help Lucy? I can think of several reasons, none of them really convincing:

ReplyDelete1. She wants to help Edward, and helping her flatter Mrs. Jennings into being her ally is a means to that end. But is it? She knows Edward doesn't love Lucy, and anything that delays their marriage increases the chance of his final escape from her (this will appear towards the end, when she is told he is married and we learned that she had hoped something would happen to prevent the marriage).

2. She is just a kind person, and helps everyone wherever she can, including Lucy, whenever the opportunity comes. But help Lucy against Edward? Elinor is wise enough to realize that this is against Edward. Not kind.

3. Because she dislikes Lucy and hates her engagement to Edward, she feels she has to bend over backward to be fair to her, either from a moral point of view, or to save her pride. This seems to me the most likely motivation.

What do others think?

I agree with your third reason, because it's exactly what I've done myself!

DeleteTruly... so have I! And looking back, years later, it seems so foolish and pitiable on my part...

Delete