Sense & Sensibility, chapter 22: A Steele Trap

In a plot-heavy narrative, we often don’t get time to just hang out with the characters. Everything has to be moving—and of course it’s a thrill watching a chess genius manipulate pieces across the board. But Jane Austen is at her best when she lets her characters speak for themselves.

Consider this chapter a case study: Lucy Steele is loathsome, uncouth, malicious, and sneaky. She makes that clear through her word choice, her behavior, and her entire approach to Elinor. I mean, the fact that she decides at all to approach Elinor rather than keep quiet and put her trust in Edward says a lot more about Lucy than Lucy hopes to convey.

Elinor already sees “[Lucy’s] thorough want of delicacy, of rectitude, and integrity of mind, which her attentions, her assiduities, her flatteries at the Park betrayed.” OH SNAP, Elinor! Tell us how you really feel. We’ve already seen a perfect example of Lucy’s ineffective simpering: it wins over Lady Middleton, but Elinor and Marianne see it for the shameless brown-nosing it really is. But they have to maintain the pretense that they are friends with the Steeles, or at least will tolerate them at Barton Park (the Steeles never visit the Dashwoods’ cottage, suggesting some pretense on their side as well).

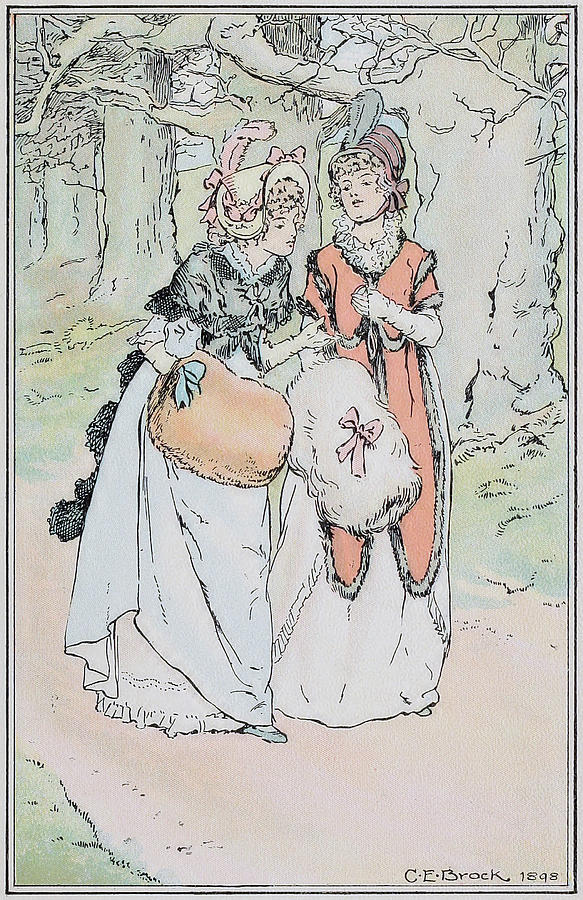

And then Lucy corners Elinor on a walk and begins her assault with an out-of-nowhere question about Mrs. Ferrars. Elinor can’t answer it, which Lucy laments—but of course Lucy has no valid reason to believe that Elinor has ever met Mrs. Ferrars, and this is all just pretense for her true motivation to speak to Elinor. As Lucy confesses, Elinor at first thinks that she’s in love with Robert Ferrars—“[a]nd she did not feel much delighted with the idea of such a sister-in-law.” Just to reinforce how much Elinor believes Edward will pop the question to her one day. But no: Lucy has been engaged to Edward. For four years. In secret.

Elinor doesn’t believe it right away (Edward never indicated that he wasn’t available), which Lucy seemed to have anticipated. As David Shapard puts it, “Lucy’s ready deployment of … proofs indicate that she has come fully prepared for this battle.” Not only does she have Edward’s mini portrait and a letter from him (proof of their engagement all by itself), but she can point to the ring he wore while staying at the cottage. (And who wants to bet that she pushed it on him knowing that he would be visiting the Dashwoods?) Moreover, her explanation about seeing Edward in Plymouth lines up with what Edward said a few chapters ago. Finally, Lucy’s explanation for why they’ve kept the engagement a secret—for four freaking years—is based around their hopes for/fears of Mrs. Ferrars, who controls the purse strings.

All this might give one the impression that Lucy is a skilled strategist. One would be wrong. Because other than the stark truth of the engagement, Lucy spends most of her time lying through her teeth. Even she knows, first of all, that inquiring after Mrs. Ferrars is a weak basis for her to break the news, as her apologies make clear. She lies about the strength of her friendship with Elinor, claiming, “as soon as I saw you, I felt almost as if you was an old acquaintance.” Then there’s all the times she sneaks a glance at Elinor to gauge the latter’s reaction. Like … she’s bad at this. Sure, she accomplishes her main goal of warding off Elinor, but she’s also tipped Elinor off to her malicious intent. If Elinor shows any emotion, Lucy is poised to make things more miserable for her. Because Lucy shows, through her insincerity, simpering, and bombardment tactics, that she thinks of Elinor as a threat. Which means that Lucy suspects Edward has feelings for her.

Lucy also reveals more about Edward, who, it has to be said, doesn’t come off looking so well here. Although she goes on about the strength of Edward’s love for her and his melancholy at having to stay away from her, it’s easy to poke holes in these declarations. They “can hardly meet above twice a-year,” you say, Lucy? What’s stopping this gentleman of leisure with his own mode of transportation from visiting you more often? “If he had but my picture, he says he should be easy”? So it’s been four whole years and he still doesn’t have a picture of you? “He was so miserable when he left us at Longstaple, to go to you”? HA. Why leave at all if he loves you so much, anyway? Shapard doesn’t hold back: “it is difficult to understand why he would have paid such attention to Elinor, or even visited the Dashwoods at all, if he truly loved Lucy.”

So how does Elinor take all this? Well, she keeps calm and carries on. Though she feels deeply, she knows that “exertion was indispensably necessary, and she struggled so resolutely against the oppression of her feelings, that her success was speedy, and for the time complete.” And since her the “oppression” she feels isn’t wholeheartedly conveyed, we don’t see how she manages this superhuman feat. It’s this aspect of Elinor’s character that irks me. There’s no nuance, no illustration of how she calls on her inner strength to maintain her mask of nonchalance. We seem to be expected to take it on faith. The only consideration that occurs to me is that Elinor has had practice in denying herself things she wants in order to serve those around her—that whole withholding theme I talked about is coming into play. But for me, this moment strains credulity.

We’re arrived at the end of Volume 1! Maybe the insight we’ll get into her thought process will change my mind.

Please consider dropping a few bucks my way if you like what I do here. Every dollar is appreciated. And check out my chardonnay-infused review of Persuasion (2022)!

Comments

Post a Comment